The extraordinary life of Harry Stokes – born c.1799 Doncaster, died 15 October 1859 Salford

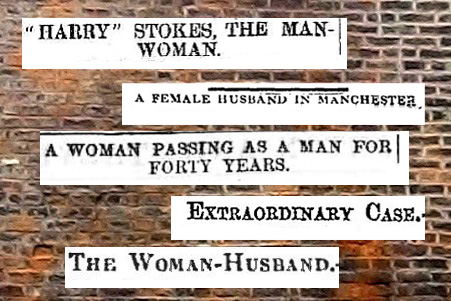

Harry Stokes’s life hit the headlines in 1838 and 1859 when he was outed as a ‘man-woman’, and ‘Manchester’s female husband’. There were lots of inconsistencies in the news reports and I hit the archives to try and separate some of the fact from fiction.

For context on Harry’s life check out how gender variant Victorians like Harry were viewed in the 1800s and how might we interpret their lives today?

Henry Stokes – or Harry as he was generally known – was born in around 1799. He assumed a male identity at a young age and began serving a bricklayer’s apprenticeship with a Mr Peacock in Bawtry, just outside Doncaster. Bricklaying was a skilled trade and Harry would typically have trained for around seven years.

Harry’s marriage to Ann Hants – Sheffield 1817

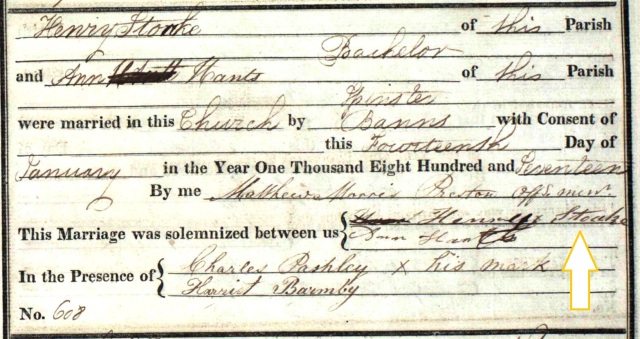

News reports told that while Harry was serving his apprenticeship he began a relationship with a young woman and the couple married in Sheffield.

There’s a record of a Henry Stoake marrying an Ann Hants on 14 January 1817 at the Cathedral Church of St Peter and St Paul, Sheffield. Check out the marriage entry below, are the scribbled out names clues that all was not what it seemed?

Image courtesy of Sheffield City Council Libraries, Archives and Information Services

Harry’s bricklaying business

The young couple moved to Manchester where Harry built up a successful bricklaying firm. News reports from 1838 highlight that Harry was a well respected tradesman specialising in chimney and flue construction. He employed eight men and an apprentice, with Ann doing the bookkeeping.

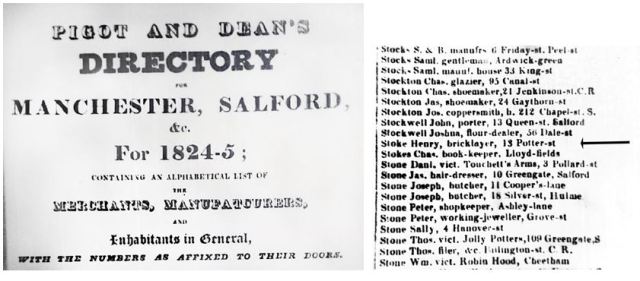

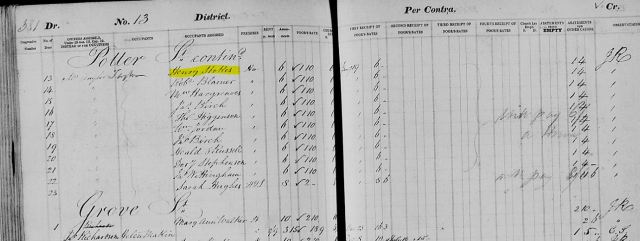

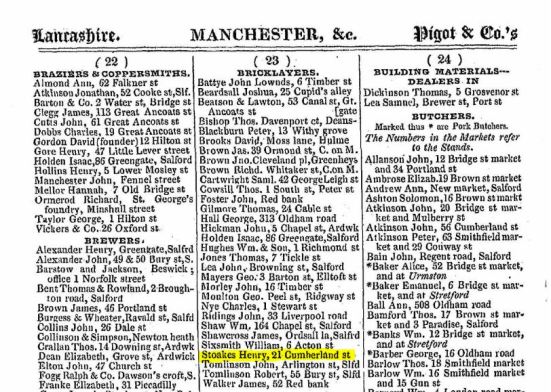

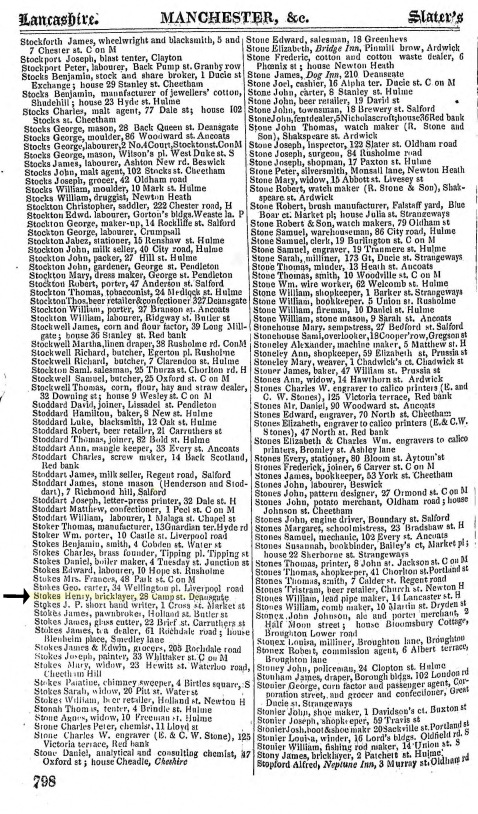

We can find Harry listed as a bricklayer in Manchester trade directories from 1824 to the 1850s . Here’s Harry’s entry in the 1824 directory: Henry Stoke, 13 Potter Street:

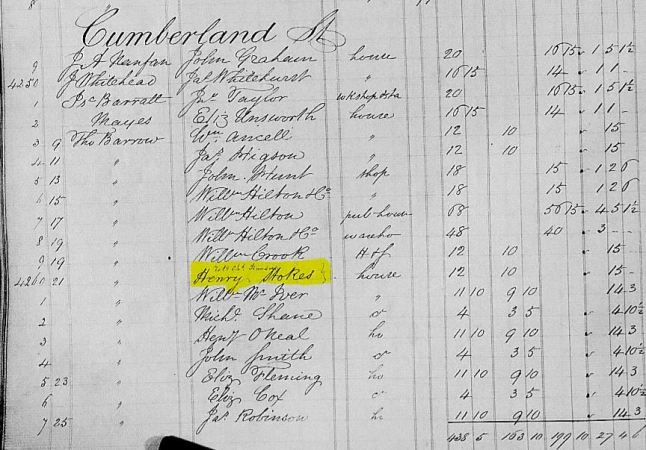

Images of rates books and trade directories courtesy of Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives, Manchester City Council.

Harry is also listed in Manchester rates books from the 1820s to 40s,with details of his council tax payments. Here’s Harry in the 1826 Manchester rates book:

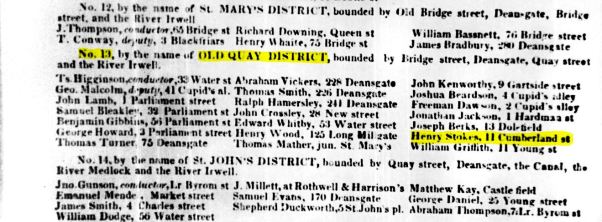

From 1824 Harry is listed as living at 13 Potter Street, from 1828 to 1830 he’s living round the corner at 11 Cumberland Street, and from 1832 to 1838 he’s listed just down the road at 21 Cumberland Street.

The rates books back up the idea that Harry’s business was doing well. For example, in 1832 Harry paid the 4 shillings annual church levy and £1, 12 shillings annual poor relief tax all in one go. Some of his neighbours paid these taxes in quarterly installments.

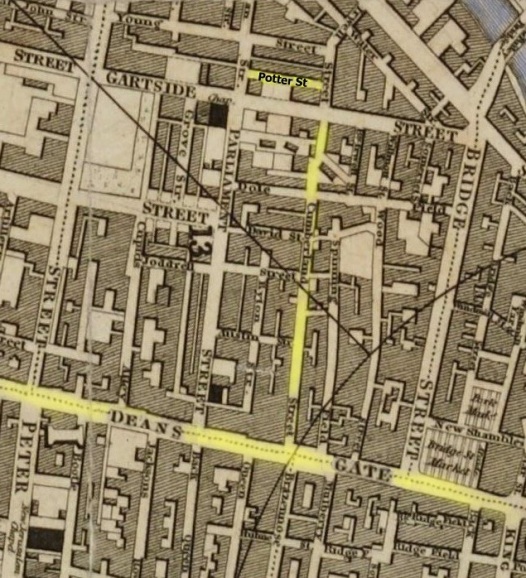

Life in the 13th District of Manchester

The area where Harry and his wife lived was known as District No 13, The Old Quay District. Nowadays it’s Spinningfields – Harry’s home on Cumberland Street was where The Avenue is today:

Pigot & Son’s Plan of Manchester, 1832

In the 1820s & 30s the district didn’t have the best reputation. In 1832 following a cholera epidemic, social investigator Dr. James Kay surveyed the area and published his findings in a pamphlet called The Moral and Physical Condition of the Working Class Employed in the Cotton Manufacture in Manchester:

“Near the centre of the town, a mass of buildings, inhabited by prostitutes and thieves, is intersected by narrow and loathsome streets, and close courts defiled with refuse. These nuisances exist in No. 13 District, on the western side of Deansgate, and chiefly abound in Wood-street, Spinning Field, Cumberland-street, Parliament-passage, Parliament-street and Thomson-street. In Parliament-street there is only one privy for three hundred and eighty inhabitants, which is placed in a narrow passage, whence its effluvia infest the adjacent houses, and must prove a most fertile source of disease. In this street also, cesspools with open grids have been made close to the doors of the houses, in which disgusting refuse accumulates, and whence its noxious effluvia constantly exhale.”

Harry’s work as a Special Constable

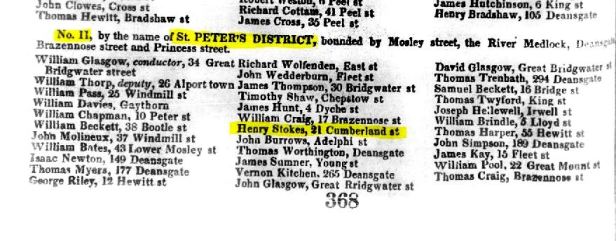

In the Public Officials section of the 1829 trade directory Harry is listed as a Special Constable for the 13th District of Manchester.

Then in the 1832 Pigot’s Manchester Directory, he’s registered as a Special Constable for the 11th District, St. Peter’s District.

Duncan Broady, Curator at the Greater Manchester Police Museum explained that in the 1820s and 30s the Deputy Constable of Manchester would recruit a reserve of men each year who could be called on to work shifts as Special Constables as and when needed. They’d help at events where there were large gatherings of people with the potential for trouble, such as protest marches and demonstrations. Harry wouldn’t have worn a uniform on a police shift, but would have been issued with a decorated truncheon which acted like a form of ID and warrant.

Special Constable’s truncheon – Manchester 1800s

In 1838, an article in the Manchester Guardian described Harry’s track record as a Special Constable. The journalist used female pronouns to talk about Harry, or referred to him as ‘the husband’.

“[Harry] was for many years a special constable, in the 13th division of that body, acting for this town; and we are assured that, on all occasions where the services of the division were required, as at elections, orange processions, and meetings of trades’ unions, turn-outs … she is remembered to have been one of the most punctual in attendance, and the most forward volunteer in actual duty, in that division. We understand that she is no longer a special constable, because she did not, on the last annual procession, held for that purpose at the New Bailey, present herself to be resworn. She was not discarded or discharged; there was no complaint against her; and probably the extension of her own business was her only motive for not resuming the danger of this office.” Manchester Guardian, April 14, 1838, p2

Here is Harry’s listing in Pigot’s 1834 Lancashire trade directory:

And here’s Harry’s final entry at 21 Cumberland Street in the 1838 rates book – not sure what the note just above his name says:

1838 – Harry’s life hits the papers

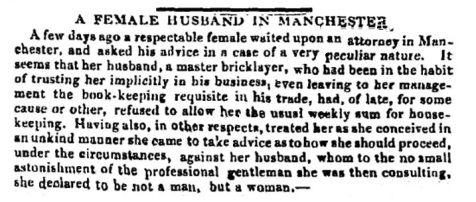

A FEMALE HUSBAND IN MANCHESTER – Article on Harry Stokes from The Observer, April 16, 1838

In April 1838, after 22 years of marriage, Harry’s wife approached a lawyer for advice on getting a formal separation and a maintenance settlement. Harry’s behaviour had recently become unbearable – he was withholding the housekeeping money, getting drunk and ill-treating her. Ann particularly wanted advice on where she stood given that her husband was not a man, but a woman. The astonished lawyer informed a local magistrate, who in turn called on Mr Thomas, Deputy Constable of Manchester for assistance.

Harry and Ann were then summoned to the police station. Harry was examined by a police surgeon who issued a certificate confirming Harry to be a woman :

“in the deputy-constable’s room at the police office, the truth of the wife’s averment to the attorney was corroborated in the most distinct and unqualified manner by Mr Ollier, surgeon to the police, who gave a certificate declaring that the individual in question was a woman… The woman-husband, we believe did not make the least attempt to deny her sex, but contented herself with stating, that her wife had only been led to make this exposure, because she had withheld from her the weekly allowance of money for housekeeping expenses…The wife has also stated, that she accidently made the discovery of the sex of her husband as much as two or three years back; but that she had kept the secret till the present time. ”

Manchester Guardian, Weds April 11 1838, p2.

Three days later, a follow-up story told how Mr. Thomas, the Deputy-Constable mediated between Harry and his wife:

“We believe that although no legal proceedings have been, or indeed could be taken in this extraordinary case. Mr. Thomas, the deputy-constable, has had several interviews with the husband, in which he has endeavoured to induce her to make some provision for the woman whom she has so shamefully deceived; and who having, for twenty-two years, filled the character of a wife, greatly benefitting the interests of the supposed husband, not only by her care of household concerns, but of the business, books and accounts, had surely some claim to compensation as servant, if she were unable by law to demand the maintenance of a wife. We believe that Mr. Thomas so far succeeded in this humane negotiation, to induce the husband to agree to give up to the wife the house in which they had resided up to the time of the discovery, with all the furniture that it contains. The wife is, therefore, still residing there; and the husband has gone to lodge elsewhere.”

The Manchester Guardian Apr 14, 1838, p2

Harry was portrayed as an eccentric hero, able to overcome normal feminine fears and weaknesses to work as a builder “a trade of more than ordinarily masculine and hazardous description”; and gain a fearless reputation working as special constable: “[duties], if the least feelings appertaining to her sex had remained, she would anxiously have endeavoured to evade”.

However news reports warned that now the secret of Harry’s “disguise” was out in the open, he’d have to start dressing as a woman or else leave town to set up business elsewhere. Harry did neither.

Street ballads about Harry

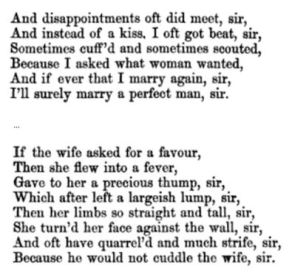

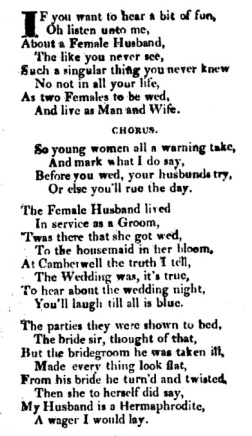

News reports tell that Harry became the talk of the town, a source of ridicule. Ballads – like a tabloid scoop sung to a folk tune – were composed about him and sung and sold in the streets.

Unfortunately there’s no record of a ballad about Harry Stokes in the Chetham’s and Central Library ballad collections. But later newspaper reports on Harry’s life give clues about the content of the songs. Harry was with his first wife Ann for twenty-two years, but somehow by the late 1850s Manchester residents had somehow developed a collective memory of how his first marriage had lasted just one day. At the inquest into Harry’s death people recalled that Harry had courted a barmaid called Betsy and they’d got engaged. On their wedding day he’d played the part of a groom well enough, but on the wedding night they’d been an terrible row. Harry was charged with assault and was sentenced to two months in jail. At his court hearing Betsy declared that she wouldn’t to live with her husband because he was really a woman.

As there is no evidence that Harry’s first marriage lasted just a day or of Harry being charged with assault, it can be seen that the ballads about Harry told this tale of a doomed marriage to Betsy the barmaid. With a third of men and half of women in 1838 having low levels of literacy, ballads, sung in local taverns and on street corners were an important source of news.

If the ballads about Harry did tell the tale of a ‘wedding night gone wrong’ they may have been based on ballads composed about James Allen, another ‘female husband’. James’s gender hit the headlines in 1829 after an accident at work. When his body was examined by a doctor it was discovered to be “that of a female”. Newspapers reported that his wife of 21 years swore that she had no idea that her “supposed husband” was of “the feminine gender”. In 1829 two ballads about James and his wife, both called ‘The Female Husband’ were printed by T. Birt of Seven Dials, they mention a wedding night gone wrong, and the ‘female husband’ thumping his wife.

Here’s an extract from one version:

…and extracts from the second version of The Female Husband ballad:

Harry and his second long term partner Francis

After separating from his first wife Ann, Harry became friendly with a widow called Francis Collins, a barmaid who served in his local beerhouse. News articles from 1859 told that Francis felt sympathy toward Harry who had become a local figure of fun. Harry and Francis moved in together in a cottage in Corporation Street, Salford. John Heaton who was Francis’s son from her first marriage was later reported as saying that he “always regarded Harry as his stepfather, and his mother assumed the name of Stokes and passed as his wife.”

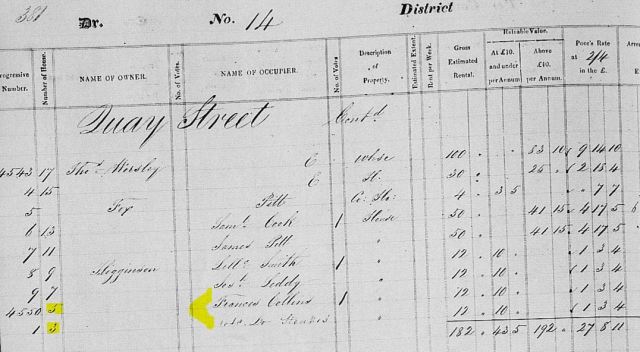

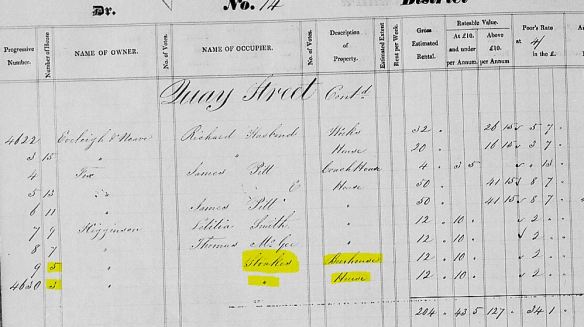

In 1840 they moved to a house at the top of Quay Street which they converted into a beer house. Here’s the rates book entry for Quay Street showing Harry and Frances living at numbers 3 and 5, but Harry’s listing looks like a bit of a scribbled afterthought

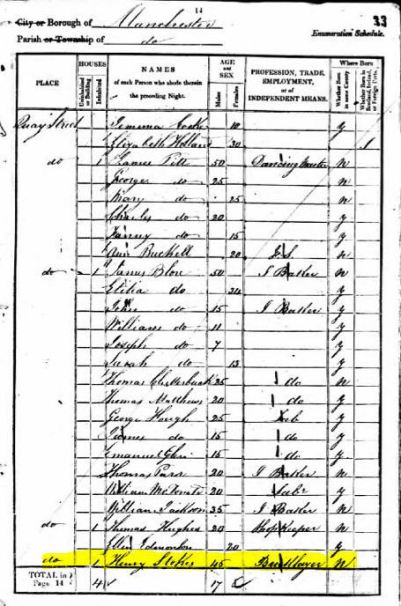

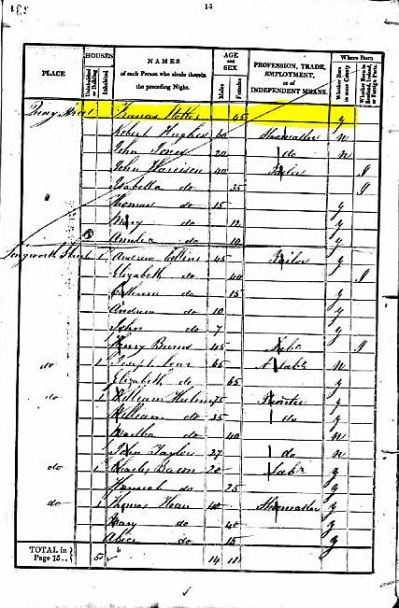

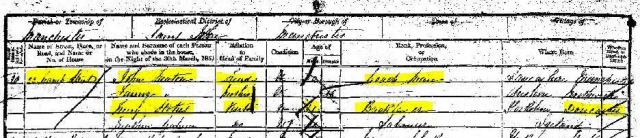

The 1841 census was taken on 6 June 1841, Francis and Harry are living down Quay Street with Francis listed under the surname Stokes. Harry is listed as a bricklayer. Both Francis and Harry are listed as aged 45 – but on the 1841 census ages were generally rounded up or down to the nearest five.

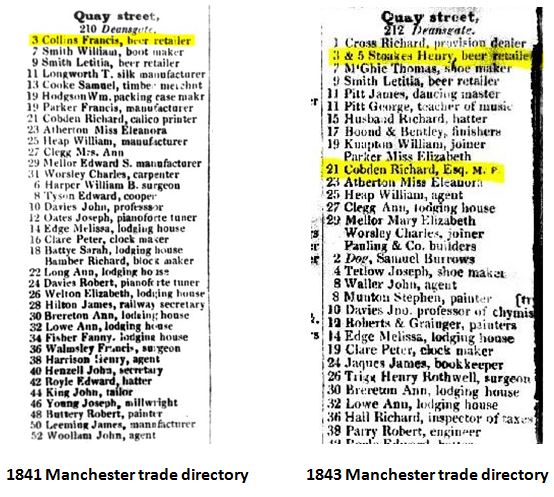

Francis Collins is listed in the 1841 Manchester trade directory, whereas Harry is listed in the 1843 directory. Check out Richard Cobden MP living a few door down from Harry and Francis.

From 1842 to 1844 Henry Stokes is listed as paying rates for numbers 3 and 5 Quay Street. In the 1843 record, the rate payer is just listed as Stoakes – perhaps some public officials were reluctant to use his full name given the gossip about him?:

By 1846 Harry and Francis were live-in landlords of a beerhouse at 22 Camp Street called the Pilgrims Rest. It was registered in the name of Francis’s son John Heaton who is listed as the rate payer and in trade directories as a beer retailer. Harry doesn’t appear in trade directories again until 1855.

Here’s the 1851 census entry for Harry, Francis and John at 22 Camp Street. John is listed as a coach driver and the head of the household – Harry is listed as a visitor. Harry is listed aged 51 and a bricklayer, with birthplace of Doncaster. Francis is listed as Fanny Heaton aged 58.

In 1852 Harry, Francis and John move their beerhouse to 28 Camp Street. John is registered here in the 1852 local trade directory as a beer retailer, and the last record of him at this address is in the 1854 rates book.

Harry is listed in the 1855 and 1856 directories as a bricklayer at 28 Camp Street. Here’s his entry in the 1855 Lancashire directory

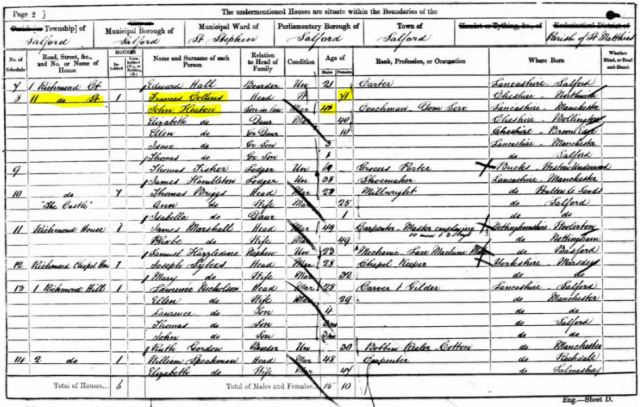

Around 1856 Harry moved to 11 Richmond Street Salford to live with Francis and John Heaton.

1859, found drowned – supposed suicide

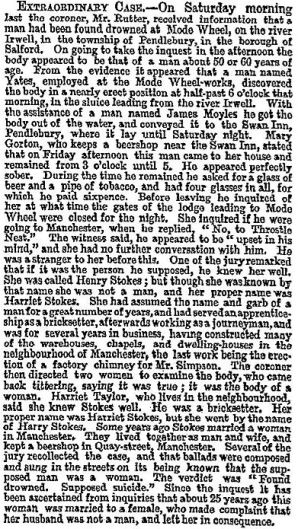

On Saturday 15 October 1859, Harry’s body was found in the River Irwell at Mode Wheel, Salford, near where Media City is today.

The inquest into his death was held at the Swan Inn, Pendlebury. The Times reported that the landlady of a nearby beerhouse said that on the eve of his death Harry had spent two hours in her pub consuming four glasses of beer and a pipe of tobacco. As he was leaving he asked what time the Mode Wheel lock lodge gates closed, and “appeared upset in his mind”. A member of the jury said that he thought the body was that of Harry Stokes who was “not a man and her proper name was Harriet Stokes”. Harry’s body was then examined by “two women who came back tittering saying it was true, it was the body of a woman”. The inquest verdict was ‘Found drowned – supposed suicide”.

Francis Collins gave a statement to the police saying that she and Harry had lived together for many years. John Heaton [actually referred to as Thomas Eaton in press reports] said that he’d always looked on Harry as his step-father.

Article on Harry Stokes’s inquest, The Times, 20 October 1858, p8

The inquest into Harry’s death was reported in the local press, with headlines such as ‘A WOMAN PASSING AS A MAN FOR FORTY YEARS’ – The Manchester Examiner; and ‘HARRY STOKES THE MAN WOMAN’ – The Salford weekly News. The stories were reprinted in papers across the country from Bristol to Whitehaven.

The papers were curious about the motives for Harry’s “deception” suggesting he adopted boy’s clothes after running away from home because of a disagreement with his father. They remarked on Harry’s physical appearance, his lack of whiskers, and short stature, and commented that “She was very full-breasted, but the shape of her womanly make was distorted by a broad strap which was buckled round her body under the arms.”

Journalists expressed admiration that Harry had “so wonderfully repressed her own feelings and natural disposition” for so many years, even exaggerating stories of his manly achievements: “in the days of the Chartist riots she was sworn in as special constable, and was made captain of her company” (the Chartism movement only began in 1838, after Harry had been outed by his first wife, and had moved to Salford). Journalists wondered whether Francis Collins had really known her husband’s secret – after all the ballads had told of how his first wife Betsy discovered on their wedding night that Harry was a woman and left him in consequence.

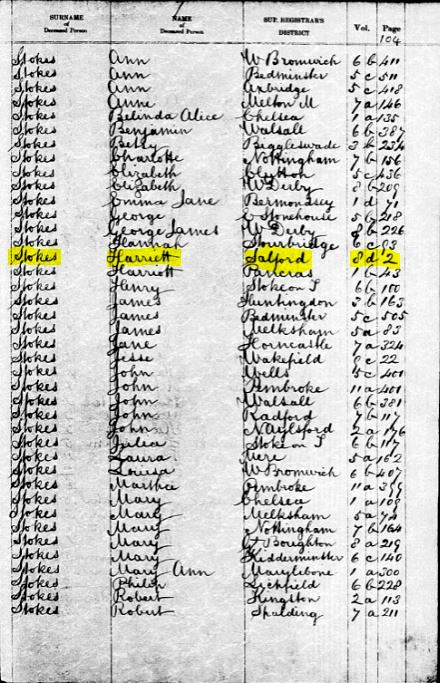

In the General Register Office death entry, Harry was listed as ‘Harriett Stokes”:

After Harry’s death Francis continued to live at 11 Richmond Street with John Heaton and his family. Here’s their listing in the 1861 census: Francis’s age is 71 and John Heaton is down as her son-in-law rather than her son.

Check out:

Newspaper stories on Harry Stokes – 1838 and 1859